For our Thanksgiving article, I wrote about the fact that caregiving can actually be beneficial to the caregiver — that there is a part of gratitude that people often overlook: allowing others the chance to show love through care. However, that sentiment is obviously not always the case, and more often, as I’ve written about many times, caregiving can be an extreme burden. If you are caring for a spouse, parent, partner, or other loved one, you may think the main medical crisis in your family is the disease they have — Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, cancer, stroke, or something else. In reality, there is often a second, quieter crisis running alongside it: what caregiving is doing to your body and brain.

Surveys and other research spotlight just how serious this is:

• Sixty-four percent of family caregivers experience high emotional stress.

• Forty-five percent report significant physical strain.

• Between 40 percent and 70 percent show clinically significant symptoms of depression.

• Caregivers report chronic conditions — including heart disease, cancer, diabetes, and arthritis — at almost twice the rate of non-caregivers (45 percent vs. 24 percent).

• Women, who provide most unpaid care, report even higher levels of stress than men.

We have been warning about this pattern for years on the Farr Law Firm blog — see the following articles:

Unprecedented Caregiver Fatigue in America — Do You Suffer from Caregiver Burnout?

Can Caring for a Loved One Be Harmful?

When Caregiver Stress Becomes Extreme

A recent New York Times opinion piece by Michelle Cottle on America’s caregiving crisis pulls the same data together and drives home the point: caregiving is not just tiring; it is making millions of people sick. You can read that article here: The Caregiving Crisis.

Caregiving Today: Unpaid, Untrained Medical Work

Most people still picture caregiving as “helping out” — cooking, laundry, rides to appointments. That picture no longer matches reality.

Today:

• More than half of family caregivers now perform medical or nursing tasks in addition to basic daily activities.

• These tasks can include managing complex medications, injections, wound care, catheter care, feeding tubes, and monitoring symptoms.

• Caregivers are usually expected to perform these tasks with little or no training, with no guaranteed backup, and often while holding down a job or caring for children.

The more involved the caregiving, the greater the strain. When you are effectively functioning as an unpaid nurse on top of everything else, your own health may pay the price.

Dementia Caregiving: A Perfect Storm for Stress and Disease

Caregiving is risky in any serious illness. When dementia enters the picture, the danger to the caregiver’s health climbs even higher.

For caregivers of persons suffering with dementia:

• Confusion, fear, and resentment from the person with dementia are often directed at the caregiver.

• Sleep is frequently destroyed by nighttime wandering, agitation, or repeated bathroom trips.

• Communication breaks down, so basic tasks — bathing, dressing, eating, taking medications — can turn into long, draining battles.

• Physical issues (falls, infections, pain) and cognitive issues (delusions, paranoia, aggression) feed off each other, creating a snarl of problems that all land on the caregiver’s shoulders.

We have highlighted these realities in many Alzheimer’s and dementia–focused articles, such as:

When Caregiver Stress Becomes Extreme

Mental Health of Caregivers Is Subject of Powerful Documentary

The Caregiving “Crisis”: Findings from a New Genworth Study

In those articles, we have shown how dementia caregiving can lead to severe depression, anxiety and, in some cases, suicidal thoughts. This is not just “more caregiving.” It is one of the most dangerous caregiving roles for the caregiver’s health.

From Stress to Disease: How Caregiving Damages the Body

The grim health statistics for caregivers are not random. There are clear mechanisms connecting long-term caregiving to disease.

Chronic stress hormones

• Constant responsibility, lack of control, and emotional strain keep cortisol and adrenaline high.

• Over time, this drives high blood pressure, weight gain around the abdomen, insulin resistance, and damage to blood vessels.

Inflammation

• Caregivers show higher levels of inflammatory markers like IL-6 and C-reactive protein.

• Chronic inflammation is strongly linked with heart disease, stroke, some cancers, and autoimmune conditions.

Sleep deprivation

• Being up at night with a loved one — and then “on duty” again all day — destroys restorative sleep.

• Poor sleep alone increases risk for hypertension, diabetes, obesity, and depression.

Immune suppression

• Stress plus poor sleep weakens the immune system.

• Caregivers get sick more often and recover more slowly from infections.

Neglected medical care

• Caregivers commonly cancel or skip their own appointments, ignore symptoms, and abandon treatment plans because they “don’t have time.”

• Small problems become major ones — advanced heart disease, poorly controlled diabetes, late-stage cancer, and more.

In Can Caring for a Loved One Be Harmful?, we described a husband so focused on caring for his wife with Parkinson’s that he ignored his own health until he was diagnosed with terminal cancer. That story is extreme, but not rare.

The Workforce Behind You: Immigrant Caregivers Holding Up the System

The New York Times article also highlights something many families only notice when they finally try to hire help: America’s long-term care system is being held up by immigrant workers.

National data show that:

• More than 820,000 immigrants work in the direct long-term care workforce (aides and nurses).

• Immigrants make up about 28 percent of personal care workers and around 40 percent of home health aides, far above their share of the overall workforce.

• The Bureau of Labor Statistics projects that demand for home health and personal care aides will grow by about 17 percent over the next decade, making it one of the fastest-growing occupations in the country.

At the same time:

• Pay in these jobs is often low.

• Conditions are physically demanding and emotionally intense.

• Turnover is high, and agencies struggle to staff all shifts.

For you and your clients, that means:

• When a caregiver finally reaches the breaking point and seeks help, agencies may not have workers available.

• Families may face long waitlists, patchwork coverage, or rising hourly rates.

• Immigration policy and workforce burnout add even more uncertainty.

You cannot safely assume that “someone will be there” to step in when you can no longer do it alone.

What This Means for You as a Caregiver or Future Caregiver

If you are already a client of the Farr Law Firm, or if you are just waking up to how serious your situation is, you may need to treat your caregiving role as a major health risk — not just a stressful chore.

• Your health is part of the care plan. If you collapse, the entire arrangement around your loved one collapses.

• You are statistically high-risk. Compared with noncaregivers, you are far more likely to develop depression, anxiety, heart disease, diabetes, and other chronic conditions.

• You cannot count on the system to bail you out at the last minute. The supply of paid caregivers is already strained and heavily dependent on immigrant labor.

From a planning perspective, that means any serious estate, long-term care, or life-care plan must address:

• How much care a spouse, adult child, or other family member can safely provide — and for how long.

• What happens if the primary caregiver becomes sick, disabled, or dies first.

• When and how to build paid care into the plan, instead of assuming family will provide all care forever.

• Whether Medicaid, Veterans benefits, or tools such as a Living Trust Plus® Medicaid Asset Protection Trust are needed so the family can afford home care, assisted living, or nursing home care without destroying the caregiver’s health and finances.

Our caregiving archive goes into these issues in detail: Caregiving Articles – Farr Law Firm.

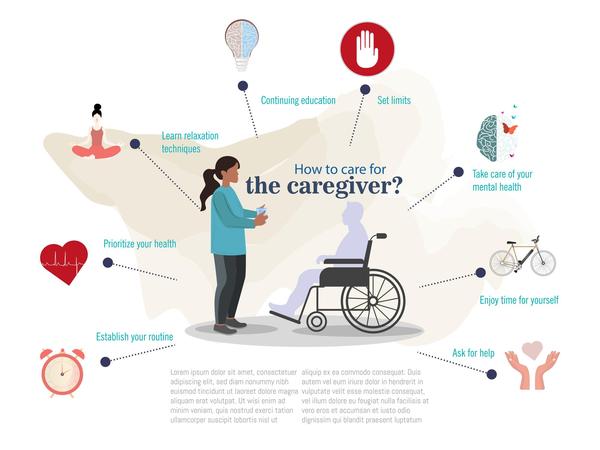

Concrete Steps to Protect Your Health Now

You cannot make caregiving easy, but you can make it less likely that it will destroy your health. That requires specific, deliberate action.

1. Admit you are at risk.

• If you recognize yourself in these statistics — exhausted, irritable, forgetting things, ignoring your own health — stop dismissing it as “just a rough patch.”

• Call it what it is: you are a high-risk caregiver, and your health is already being affected.

2. Put your own medical care back on the calendar.

• Schedule overdue physicals, lab work, and specialist appointments.

• Tell your doctors directly that you are a caregiver; that context matters for interpreting symptoms and assessing risk.

3. Use respite and paid help before you crack.

• Even a few hours a week of home care or adult day care can reduce stress and give your body a chance to recover.

• Waiting until you are in crisis is a bad strategy — by then your health may be badly damaged, and agencies may not be able to staff your case quickly.

4. Create a written care and backup plan.

• Document your loved one’s medications, routines, doctors, and key contacts in one place that others can use if something happens to you.

• Spell out who steps in if you are hospitalized or suddenly unable to continue.

5. Get proper legal and financial planning in place.

• Make sure your powers of attorney, wills, and, where appropriate, trusts are up-to-date.

• For many families, planning for Medicaid, Veterans benefits, and asset protection is essential so that paid help becomes financially possible before the caregiver is totally burned out.

• In The Caregiving “Crisis”: Findings from a New Genworth Study, we show how advance planning can reduce stress and prevent emergency decisions based on panic.

6. Recognize when home care is no longer safe.

• If your loved one is aggressive, wandering, refusing medications, or awake most nights, home care may no longer be safe or realistic.

• Planning for assisted living, memory care, or nursing home placement is often not “giving up.” It is sometimes the only way to protect both the patient and the caregiver.

Stop Trying to Be the Hero Who Never Breaks

There is a powerful cultural script that the “good” spouse or adult child does everything, never complains, and never needs help. That script, sadly, is sometimes killing these loving and well-intentioned caregivers.

Trying to live up to that ideal is how caregivers end up with heart attacks, strokes, major depression, or other serious illnesses — sometimes dying before the person they are caring for. It is also how care recipients end up in chaos when the caregiver suddenly cannot continue.

If you are already a caregiver, or you see that role coming in the near future, the safest move is to face the risks now and build a real plan. That means:

• Treating your own health as nonnegotiable.

• Using legal and financial planning to bring paid help into the picture and to plan realistically for facility care when needed.

• Recognizing that a system built on overworked family caregivers and a stretched immigrant workforce will not magically catch you if you fall.

The caregiving crisis described in The New York Times is real. The disease burden on caregivers that you have been documenting for years is real.

If you are caring for someone you love — or expect to be — now is the time to put a comprehensive plan in place that protects you, as well as the person you are working so hard to help.